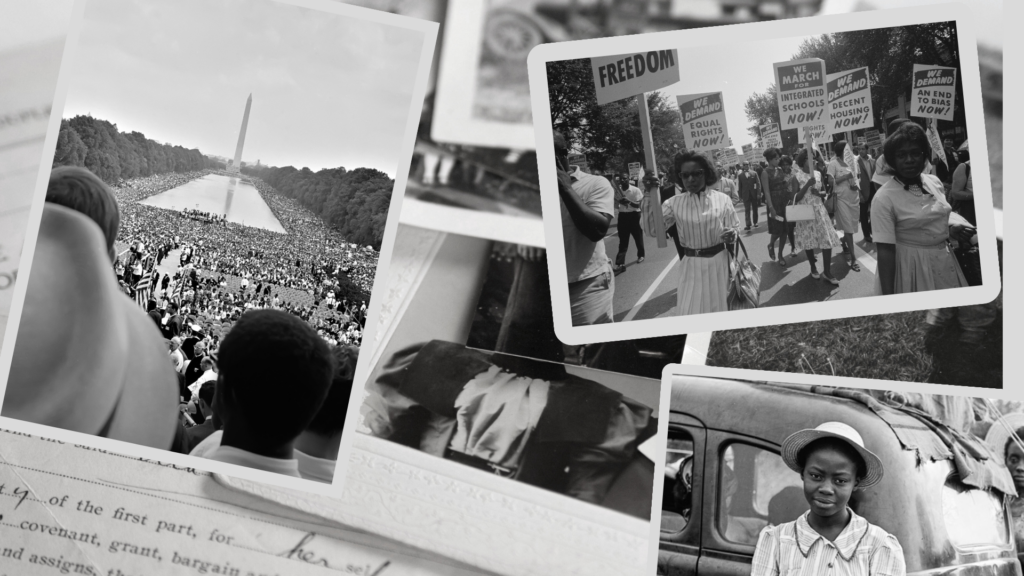

In honor of Black History Month, we’d like to recognize some of the individuals who advanced our understanding or advocacy of aging and disability. Too often, the names of people of color are missing or downplayed in our history. Here are five whose names and stories we do know, and who deserve to be remembered and celebrated.

Eliza Simmons Bryant, the daughter of a freed slave, was a lifelong humanitarian who established the Cleveland Home of Aged Colored People in the late 1890s after observing that people of color were excluded from nursing homes due to segregation.

Solomon Carter Fuller was a pioneering neurologist, psychiatrist, pathologist and professor who contributed important research into Alzheimer’s disease in the early 20th century, when the disease was poorly understood.

Jacquelyne Johnson Jackson, PhD, was a Civil Rights activist and pioneering researcher into aging in black Americans. She drew attention to the lack of data and study of aging people of color and was among the first to recognize the intersection of racism, economics and isolation in the black aging experience.

Brad Lomax was a Civil Rights and disability rights activist who helped lead the “504 Sit-In,” in San Francisco in 1977, which led to the passage of Section 504 of the U.S Rehabilitation Act, creating and extending civil rights to people with disabilities.

Sylvia Walker, PhD, overcame ableism, sexism and racism to become a lifelong champion of the rights of people with disabilities. Much of her research as a Howard University professor is credited with informing the American Disabilities Act and helping it to be passed into law. She cofounded the American Association of People with Disabilities (AAPD) as well as what’s known today as the Center for Disability and Socioeconomic Policy Studies at Howard.

Hobart C. Jackson, Jr. spearheaded the creation of what is today called the National Caucus and Center on Black Aging (NCBA). Throughout his career he fought to raise awareness and address the inequalities that impact black aging. As NCBA says, he “laid the cornerstone and began the dialogue for change as it pertained to the programs and services that benefit low-income Older African Americans.”